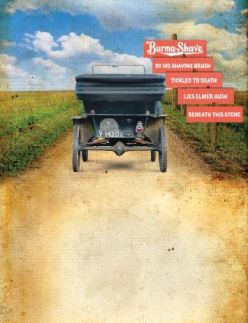

During the era when motorized travel became common and roadways more accommodating, Burma-Shave signs delivered a message and a smile.

By Juddi Morris

April 2014

In 1925, when Model T Fords were making their way down the assembly line, a string of tidy, little signs advertising a brushless shaving cream popped up along the roadsides. Within a few years, Burma-Shave signs with catchy rhymes blanketed the edges of two-lane roads across the United States.

Travel was slower in those times, but some said that it was more fun, thanks in part to those Burma-Shave signs. The signs were a huge advertising success, too.

Folks liked this method of advertising, which became even more prevalent in the 1930s. Everyone needed a lift during those hardscrabble Great Depression times. Most ads and illustrated signs were dull and warned of what would happen if you didn’t use a company’s product. Listerine hinted that almost everybody had bad breath and should gargle with its mouthwash. Absorbine Jr. reminded people to watch out for the dangers of athlete’s foot. Ex-Lax nagged folks about their bowels. Lifebuoy warned of the perils of body odor. Amidst all this dreary advertising, Burma-Vita, which produced Burma-Shave, came out with cheerful, corny signs that made people laugh.

The signs usually were arranged in a sequence of five or six, placed 100 feet apart. Farmers or landowners were compensated by the company for allowing them to be planted on their property. The ads were a cash crop that didn’t have to be fed, watered, milked, plowed, harvested, or marketed. Burma-Vita even took responsibility for the upkeep of the signs.

The company’s advance men cruised along the highways, selecting the best spots to place the signs. Leonard Odell, son of company founder Clinton Odell, worked one summer sinking the posts and putting up the signs. He recalled erecting this set:

Old McDonald

On The Farm

Shaved So Hard

He Broke His Arm

Then He Bought

Burma-Shave

After finishing the job, Leonard backed up his truck, shifted into low gear, and cruised past, checking the proper placement of the signs. Everything looked fine, he thought; the signs were straight and easy to read. Then he glanced at the mailbox and froze. The farmer’s name was McDonald!

“I didn’t know what to do,” he said. “I figured the farmer could get his feelings hurt or get mad and throw a fit. I worried about whether I should take it down or not. Well, I prowled around and found him down at the barn doctoring a sick horse. When I hemmed and hawed about the sign being about Old McDonald and his farm, he just stood with his arms folded over his chest and stared at me. Finally, he bent over, bellowing with laughter. Turned out he had a swell sense of humor and got a big kick out of the whole thing.”

The Burma-Shave signs were sturdy, but they required maintenance. Rodents chewed the wood. Cows didn’t gnaw on the signs, but they loved to rub against them. It didn’t take long before the rubbing by these thousand-pound animals would cause the posts to tilt sideways. Sometimes people would bag one with a gun, filling it with bullet holes. Local kids often tried to wrestle them to the ground or mix up the verses.

The signs’ greatest enemies, though, were horses. They used them as back scratchers, moseying beneath the signs to do so. After too much equine scratching, the posts would snap off and the signs would fall to the ground. But the company worked out a solution. They raised the signs from 9 feet to 10 feet.

As time passed, the horse problem disappeared, as did the horses in the fields. As farming methods improved, so did the prospects for the signs, since tractors don’t itch and then scratch.

For years, these ham-fisted little verses were one of the best advertising campaigns ever conceived. That would begin to change, though, with the advent of high-speed automobiles and superhighways, as motorists were traveling too fast to read the little red signs. Another factor in their disappearance was that Phillip Morris bought Burma-Vita in 1963. The company had big plans for advertising, which did not include signs along the side of the road. Glitzy television spots would reach millions of people in a way the verses never could.

Word got out that the signs would be removed and the big Burma-Shave trucks hit the roads for the last time. Taking down the signs turned out to be a time-consuming job. Many posts were difficult to remove after being in the ground so many years. Drivers flashing past in their cars were saddened to see the uprooting. A happy part of their past was disappearing before their eyes.

As people learned that the signs were being removed, they trespassed into fields, waded through creeks, and climbed fences to yank out sets that eventually would become collector’s items.

Burma-Shave signs have been gone a long time now, but they still live in the memories of folks who read them aloud as kids, jouncing along some road in the family sedan. It may sound low-key now, but it was great family entertainment as Mom, Dad, and the kids took turns reading aloud signs as they motored past.

Following are some examples of Burma-Shave signs:

Beneath This Stone

Lies Elmer Gush

Tickled To Death

By His Shaving Brush

Burma-Shave

Congressman Pipp

Lost The Election,

Babies He Kissed

Had No Protection

To Win – Use

Burma-Shave

Man Passes Dog House

Dog Sees Chin

Dog Gets Out

Man Gets In

Burma-Shave

The Wolf Is Shaved

So Neat And Trim

Red Riding Hood

Is Chasing Him

Burma-Shave