Pioneer orchards and geological wonders await visitors at this less-crowded national park in south-central Utah.

By Ann Bush

August 2020

Almost a month after returning from a 5,000-mile road trip to South Dakota and back, I’m standing in the kitchen of my Texas home, pulling the last apple from my tattered, well-traveled sack. The apple’s sweet smell floods my senses with memories of an out-of-the-ordinary adventure during the journey.

Hickman Bridge, a natural arch, is accessible via a 2-mile hiking trail.

This was my fifth annual trip to visit relatives and explore America since retirement, and this time, I slowed down in Utah for almost a month. Camping along the way, I visited all the famous parks touted in flashy brochures, on billboards, and on my friend’s must-see list, but I found that Capitol Reef National Park was rarely mentioned. Following a hunch, I detoured off the main tourist-driven highway and headed toward the park. One sunlit September day, I found myself in the center of Utah, in an apple orchard snuggled deep in a red rock canyon.

On the surface, Utah often appeared barren and lifeless as I drove from place to place. But I paused to look closer and discovered a location full of activity of the non-tourist kind. Variations in topography, geology, elevation, and precipitation combine to create seven zones, resulting in a patchwork of pinion and ponderosa forests, grasslands, shrubs, canyons, and millions of very large rocks. Capitol Reef alone hosts more than 100 species of mammals, reptiles, fish, and amphibians, along with 239 species of birds and 900 species of plants. The movement of underground plates has created Utah’s unusual landscape. To protect it for future generations, Utah hosts five national parks and has established many state-preserved forests and lakes.

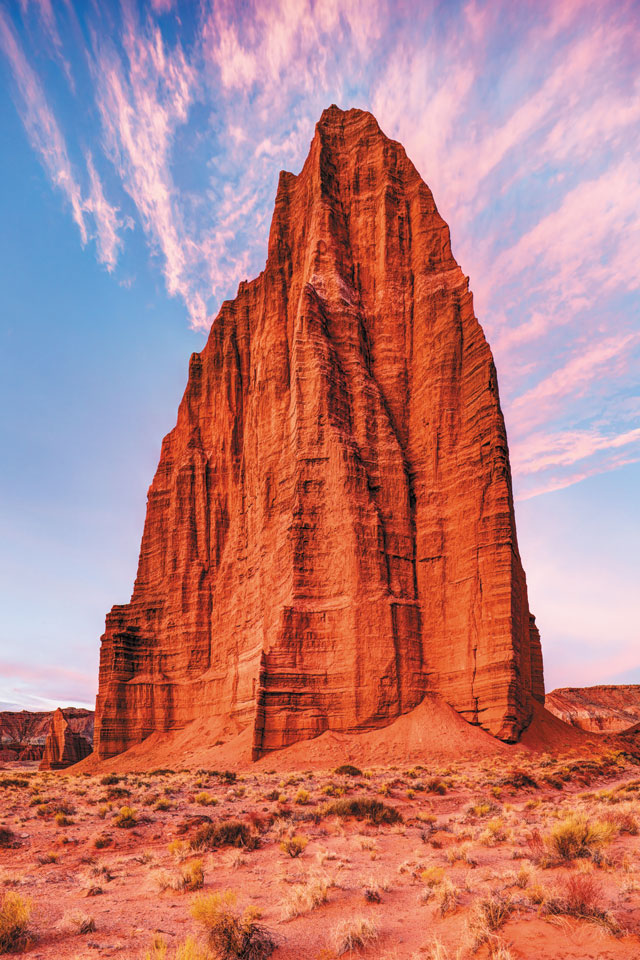

What makes Capitol Reef unique is how the canyon was formed. Millions of years ago, a massive mountain-building event caused an ancient fault to open, creating a one-sided fold of rock, or monocline, which was named the Waterpocket Fold. This elongated fold with one steep side in an area of otherwise horizontal layers was lifted more than 7,000 feet — and it is still moving. The Waterpocket Fold is reportedly the longest exposed monocline in North America.

Burr Trail Road, site of Long Canyon.

Considered a “wrinkle in the Earth’s crust,” the Waterpocket Fold is nearly 100 miles long. It creates a spectacular canyon inside Capitol Reef National Park. One of the park’s most striking icons is a large, white ball of rock that can be seen for many miles. Early settlers were reminded of the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C., and named the rock Capitol Dome. From the east, the Waterpocket Fold appears to pose a barrier to travel, much like a barrier reef in an ocean. Both formations later inspired the name of the park.

Fifteen hiking trails traverse Capitol Reef. Varying in length from a quarter mile up to 10 miles round-trip, all offer incredible views and canyon experiences. My favorite trail rambled along the canyon floor following the river, where I saw peregrine falcons soaring above. Other, more strenuous trails guide the robust hiker to dramatic cliffs with drop-offs that give goose bumps but offer panoramic views of the Waterpocket Fold.

Rare bighorn sheep strolled along the canyon walls on the Grand Wash trail, a dry streambed that becomes awash with a horrific flash flood when it rains. The Capitol Gorge trail was once the main gap in the rugged monocline and served as the primary travel route for American Indian tribes and Mormon settlers. Today, the main road through the canyon is Utah’s Scenic Byway 24. Another appropriately named route, Scenic Drive, branches off from the byway and is especially popular with bicyclists. This 8-mile paved road also is suitable for passenger vehicles and RVs up to 27 feet long. Park literature estimates that exploring Scenic Drive and the dirt spur roads, Grand Wash and Capitol Gorge, takes about 90 minutes round-trip.

Other formations in the park.

On the west side of the park, not far from the visitors center and entrance, are the first signs that humans once lived in the canyon. Petroglyphs (carvings) and pictographs (paintings) dating from A.D. 300 display their lives in stone. Hunted animals such as elk and bighorn sheep are drawn perfectly on the stone. Other images are unclear and, even today, tribal leaders and historians debate their meaning. Why the inhabitants left the canyon remains a mystery.

By now you may be asking, “What about the apple trees?” Pioneers in search of religious freedom arrived in the area in the early 1880s and discovered a deserted canyon. However, as farmers, they immediately recognized what the natives saw in the canyon’s ability to gather and store water. They settled in the center of the canyon and followed ancient tribal methods of using the porous limestone to gather and store water; this resulted in a slow, natural irrigation system and created some of the most fertile land in Utah. The soil, climate, and protection from harsh winds by canyon walls provided the perfect environment for fruit and nut trees. Soon, a modest community was created and named Fruita.

The dirt road, built by hand and altered by rain, became exceedingly rocky. Often, it was washed out by flash floods. That made travel to surrounding towns difficult, forcing the isolated community to become self-sufficient. Residents built their own schoolhouse, blacksmith shop, and community center. The “post office” was a large cottonwood tree, dubbed the Mail Tree. Mail was delivered by wagon from the nearby town of Torrey. Outgoing mail was hung on the tree and replaced with new mail every three weeks. The tree still stands in the picnic area.

The Gifford House, in the Fruita Rural Historical District, contains period items and photos.

Once Capitol Reef was designated a national monument in 1937, third- and fourth-generation residents in this area began to disband, and the last family left Fruita in 1969. It became a national park in 1971. The few buildings that remain are listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The Gifford House is now a lovely gift shop decorated with period items and includes a photo gallery from Fruita settlers.

The historic orchards continue to thrive. Approximately 2,000 fruit trees of many varieties are tenderly preserved and managed by National Park Service employees, who use the same irrigation practices as the pioneers.

During most of the year, park visitors are permitted to pick fruit from a designated orchard, which varies depending on the season. If you take only a couple pieces of fruit, there is no charge. Otherwise, you pay by the pound at the visitors center. A few locals told me the cherry trees are especially beautiful during the spring flowering season in late February, with fruit ready for picking in early May. The peaches and plums are ripe sometime in June, and the apples were waiting for me in early September.

I didn’t hesitate for a moment, filling a bag from bushy apple trees whose low-hanging branches were weighed down by green and ruby orbs of flavor. I was in good company; families around me also enjoyed the orchards, some on day picnics. Fat robins ignored me as they slurped up worms in apples lying on the ground.

The park’s Fruita Campground, sometimes called “an oasis within the desert,” has more than 70 shady spaces placed near and sometimes inside the orchards. Each site has a picnic table, as well as a firepit and/or an aboveground grill, but no individual water, sewer, or electrical hookups. An RV dump and potable water fill station are available. Rest rooms have running water but no showers. The campground is open year-round, with campsite reservations taken from March 1 through October 31. A campground map on the park’s website provides site lengths.

Utah’s Scenic Byway 24 and a spur road, Scenic Drive, wind through the heart of the park, taking visitors through a geologic wonderland.

Other camping options that offer shady sites are found in the lush Dixie and Fishlake national forests surrounding Capitol Reef National Park. To the south are Singletree, Pleasant Creek, and Oak Creek campgrounds. To the west: Sunglow Campground. Clean, family-owned RV parks are in nearby towns. Numerous other campgrounds are located along State Route 24 and in nearby Torrey. All campground information can be found on www.nps.gov. To make a reservation at Fruita Campground, visit www.recreation.gov.

Capitol Reef is open year-round, but winter conditions are much different in the park, when up to 20 inches of snow and icy roads can be expected. During my September stay, evening temperatures dropped to the low 40s. During the summer, be prepared for a very hot sun, as most trails offer little shade. Updated weather conditions can be obtained by calling the park (see box at left).

Back home, I watch a bright red cardinal the color of my apple out my kitchen window, and I remember the ancient pictographs and tattered photos displayed on the Gifford House walls, forever capturing the grim faces of hardworking people. Living in a canyon in the middle of a high desert had its challenges. Enjoying the final morsel of my apple, I silently thank the tenacious residents of this distinctive canyon who left their best to following generations of explorers.

Park Tips

Capitol Reef National Park Visitors Center

52 West Headquarters Drive

Torrey, UT 84775

(435) 425-3791

www.nps.gov/care

The visitors center is on the west side of the park, at the junction of Scenic Drive and State Route 24. Its first-class displays offer insight into the area’s history, and the staff is happy to provide information about fruit seasons and which orchard is ready to harvest; or, check the park website for harvest information.

Trail difficulty ranges from easy to moderate; most trails reach canyon plateaus with spectacular views. A sturdy hiking pole is recommended to help navigate rocky paths. Take your bicycle, as the Scenic Drive is one of the most popular bike roads in Utah, because it is a dead-end road with less traffic. The Gifford House Store and Museum is open from March 14 through October — be sure to stop there first thing for a warm and delicious fruit pie to fuel your exploring.