From gun-toting clerks in a mail car to the gentle sway of a Pullman sleeper, the California State Railroad Museum gives visitors a taste of life on the tracks.

By Richard Bauman

November 2021

When you hear the term “railroad museum,” it all too often conjures up the image of dormant railcars and dusty old engines lined up unimaginatively. Well, you’ll soon forget that mental picture when you visit the California State Railroad Museum in Sacramento. The buildings within the complex in Old Town Sacramento offer 225,000 square feet of railroading history. Some of it is old; some not so old; some nearly new.

The railroad helped build California, so building the railroad was both a significant achievement and a historic event.

What the museum isn’t is a stagnant display of railroad memorabilia. Instead, you walk through a railroad construction camp of the early 1860s, feast your eyes on one of the first locomotives in California, and literally feel the gentle swinging and swaying of a Pullman sleeping car of the 1930s.

The best way to start a tour of the museum is by watching two audiovisual presentations that offer a perspective — one depicting the history of railroads, the other documenting how railroads helped build the country. The westward growth of the United States in the 1800s was generated by a lot of things, but none more important than the completion of the transcontinental railroad. With tracks stretching across the plains and deserts and mountains, faster and safer passage west became a reality.

Before the rails crossed the country, people on the East Coast who wanted to go to California had their choice of two modes of transportation. Assuming they could afford the fare and had the time, a multi-month sea voyage was available. The other way to get to the West Coast was by wagon train. Either way, it was an arduous trip. Thus, most people only dreamed of heading to California. But with the arrival of the transcontinental railroad, they could make their dreams come true.

Ask any number of people to name the man who sparked the building of the first transcontinental railroad, and Theodore Judah probably won’t be mentioned. Yet it was his foresight and vision that got things underway.

Judah built California’s first railroad in 1855. It was, in fact, the first railroad west of the Mississippi River. Though it stretched just 22 miles between Sacramento and Folsom, it changed the trip from a daylong trek, at best, to a mere few hours. With that railroad successfully under his belt, Judah made the seemingly preposterous proposal of spanning the Sierra Nevada and running railroad tracks all the way across the country.

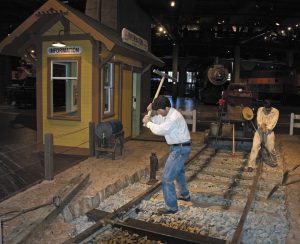

The museum depicts what life was like for those who laid the rails.

To build such a railroad would take money — lots of it. Thus, Judah went about finding some wealthy partners. He managed to convince four of the wealthiest men in the state — Collis P. Huntington, Mark Hopkins, Leland Stanford, and Charles Crocker — to join with him in the venture. On January 8, 1863, Judah broke ground at the foot of K Street in Sacramento, launching the world’s first transcontinental railroad. It didn’t take long, however, for Judah to lose control of his dream. In the end, the “Big Four,” as they came to be known, squeezed him out and took over.

It’s appropriate, then, that a trip through the California Railroad Museum starts in a diorama of an 1860s railroad construction camp. Within the display are Judah’s surveying tools, a railroad construction worker’s tent, and depictions of the living and working conditions of those building the railroad east.

The star of that exhibit is Gov. Stanford, the Central Pacific Railroad’s first engine. Restored to “showroom” condition, its gunmetal-gray body, brass trim, and huge headlight shimmer in the spotlights aimed at it.

Though the museum displays 21 different locomotives and cars — from wood-burners to streamliners — it also includes dozens of exhibits dealing with all aspects of railroading. There are examples of tools, instruments, and other railroading paraphernalia. Passenger rail service often included elegant dining; thus, the dining car exhibit conveys the concept of stylish meal service. It was the hallmark of each railroad company to have custom-made china for each of its premier trains. In the dining car, several tables are outfitted with examples of railroad china. Each design is identified with the company’s name and the train in which it was typically used. The exhibits also include such things as silver water pitchers and even a set of chimes for summoning a waiter.

The Gov. Stanford

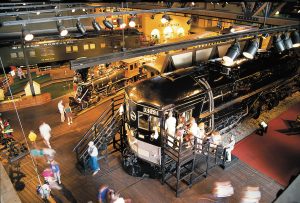

One of the largest displays is the Southern Pacific locomotive No. 4294. It is as massive as the Gov. Stanford locomotive is handsome. The unusual “cab-forward” design of No. 4294 sets it apart from most locomotives of its era. Designed for use in the Sierra Nevada, this coal-black mammoth weighs a staggering 1 million pounds.

Southern Pacific was the only major railroad in the United States to use cab-in-front locomotives. The design had multiple benefits for a train’s crew. It allowed the engineer and fireman superior visibility of the tracks, and it also prevented smoke and heat from entering the cab, which was especially important in tunnels.

Built in 1944, No. 4294 was one of the last steam-powered locomotives in service. Its 6,000-horsepower steam engine was stilled in 1956 when the huge machine was retired. The sleeping giant is a maze of massive castings, forgings, pipes, tubes, and valves. A plumber’s nightmare, to be sure. You can’t help but admire the maintenance crews who kept locomotives like No. 4294 running, and the engineers who drove them.

A few dozen feet away from the massive engine is the Pullman car “St. Hyacinthe.” At first glance, it looks like another interesting, yet static, display. But looks can be deceiving. As you step onto the car’s boarding platform, you know something is different. There seems to be a gentle, almost indiscernible swaying motion. As you step into the car proper, there’s no doubt about it. The car is moving.

The swaying of the car becomes distinct; it’s designed to give visitors the illusion of rushing through the night at 60 to 80 mph. You can virtually feel the wheels clicking over the rails and see light flashing by through the car’s frosted-glass windows.

The museum displays 21 locomotives and cars, including the unusual Southern Pacific cab-forward locomotive.

The St. Hyacinthe was the ultimate in fast, comfortable rail travel during the 1930s and 1940s. It originally saw service on the Canadian National Railroad. Substantial seats gave passengers a luxurious ride. And at night, the seats were transformed into beds.

Admittedly, the seats were more ample as seats than as beds. Stretching out in one of these beds wasn’t easy for anyone much over 5 feet tall. They were definitely more comfortable if you were small of stature.

A costumed conductor stands aboard the car to demonstrate how the seats turned into beds and how an upper berth folded down from the car’s ceiling. He also explains how passengers were almost tucked in by porters when they retired for the night in this car. Some beds are made up, complete with mannequins. The car also includes examples of private compartments that by the standards of 90 years ago were considered lavish.

Across the aisle from the St. Hyacinthe is a piece of railroading history that disappeared in 1967: the railway post office car. After taking on a load of mail in one city, postal clerks — with guns on their hips — quickly sorted mail in such cars for transport to cities down the line. The mail for each city was placed in canvas bags and tagged for its drop point.

Trains usually didn’t even stop when dropping off the mail. Instead, the door to the mail car was opened and the mail bag was pushed out, where a waiting postal worker picked it up and hauled it to the local post office for delivery to residents and businesses. Depending on the line, it wasn’t uncommon for a letter mailed in the morning to be delivered that afternoon to a town a couple hundred miles away. That was true express mail, and at no extra charge. Walking through the museum’s mail car, which saw service on the Great Northern Railway, visitors can appreciate the diligence and efficiency of railroad mail clerks.

The museum is a family-friendly destination, with attractions that spread beyond the main building.

The California State Railroad Museum is a world-class facility and an affiliate of the Smithsonian Institution. In fact, it’s the largest railroad museum in the United States, and some say the largest such museum in the world. It can take some time to get through it all, but tours are self-guided. You can spend as much time as you like at an exhibit, either studying it in detail or only casually checking it out. To really appreciate all the museum has to offer, you’ll probably want to plan on several hours exploring the major exhibits and getting the flavor of railroading history.

If you want even more, the museum has a library that allows access to its documents collections, innumerable railroad history and reference books, as well as numerous periodicals. It also is adjacent to a reconstructed passenger station, railroad freight depot, and other buildings from the 1800s that make up Old Sacramento State Historic Park.

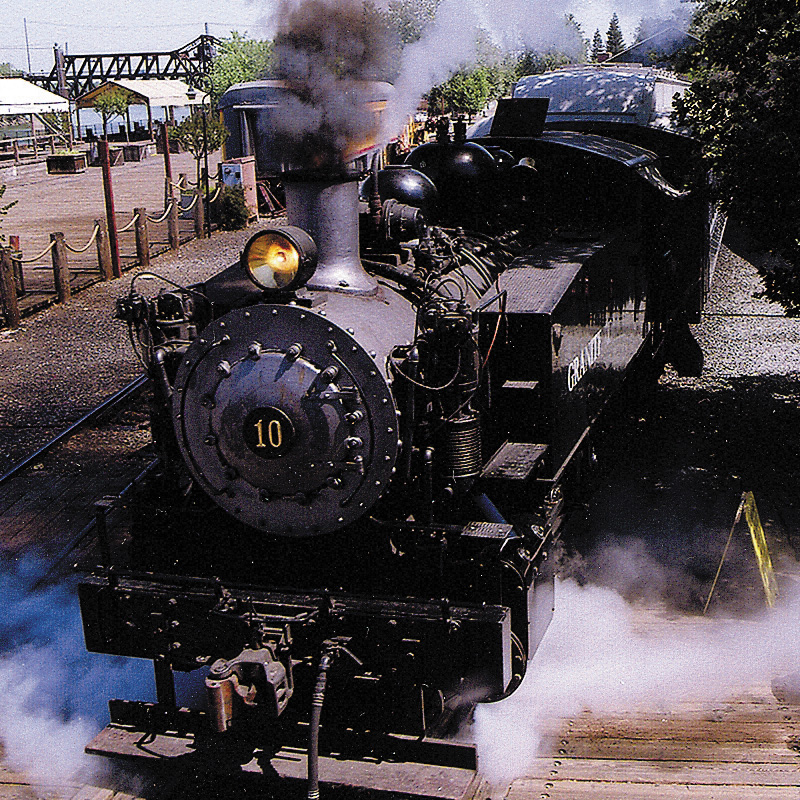

To experience railroading firsthand, try a 50-minute round-trip excursion along the scenic Sacramento River. The train is pulled by one of the museum’s historic steam or diesel locomotives. Tickets for the train ride are separate, but it’s worth the ride.

The California State Railroad Museum in Sacramento.

Information

California State Railroad Museum

111 “I” St., Sacramento, CA 95814

(916) 323-9280

www.californiarailroad.museum

Admission

Adults – $12

Youth – $6 (ages 6-17)

Children – free (ages 5 and under)

Hours

Daily from 10:00 a.m.-5:00 p.m.

(except Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Year’s Day)