Fire can consume an RV in a matter of minutes. Having a plan and the proper tools to deal with a fire can save your RV — and your life.

By Mark Quasius, F333630

December 2021

Man’s quest for fire has been around since the beginning of time, and fire can be a good thing. It can be used to cook food, heat your living space, or add a bit of ambience to a living space or a campsite. However, fire represents a risk that RVers need to keep top of mind. An RV fire can spread in a fast and furious manner, leading to devastating damage, injury, and even loss of life.

RVs have numerous potential sources of fires — RV refrigerators, propane appliances, gasoline or diesel engines, electrical wiring that takes a beating when traveling on less-than-ideal highways, etc. So, it’s important for every RV owner to develop a safety plan that covers how to deal with a fire. This involves fire extinguishers, as well as the necessary detection devices and an escape plan.

Your First Decision

If a fire breaks out, you’ll be faced with an important and immediate decision: Fight or flight. Do you stay and try to put out the fire, or do you get out and wait for the fire department? Your safety and that of your loved ones should always be your highest priority. You can replace your RV and the stuff in it, but you can’t replace someone’s life. And it’s important to know that the most common cause of death in a fire is not from the flames but from the smoke and the toxins created by burning material — especially the synthetic material common in today’s RVs.

Still, it’s a natural reaction to want to try to douse a flame, so a bit of forethought can help you make the best decision when you’re under pressure and the clock is ticking. It may be possible to handle a small fire with an extinguisher, but if the fire is larger, or if the fire prevents you from accessing an extinguisher, it’s time to exit the RV.

Creating and practicing an escape plan is crucial. Smoke and heat build up fast during a fire, so it’s vital to know where the exits are. Practice getting to them so it becomes second nature. Exiting via the entry door is the ideal choice, and some Type A motorhomes even offer optional emergency egress doors. Still, you may need to go out through one of the emergency exit windows. However, these are not always as simple as they seem. Getting to them — and getting through them — can be a challenge. This is something you should practice, because you won’t have time to figure it out during an actual fire.

Be sure to open the exit windows a couple of times a year to make sure they still function properly. Depending on the type of window, it may be a good idea to create a sturdy wooden prop to hold the window off of you as you exit. It’s best to go out through the window feet first and belly down. The drop to the ground can be long. Some people move a picnic table next to the emergency window to lessen the distance. Others carry an emergency ladder, but deploying it can take time — time you may not have.

Remember, time is not on your side in an emergency.

Fire Basics

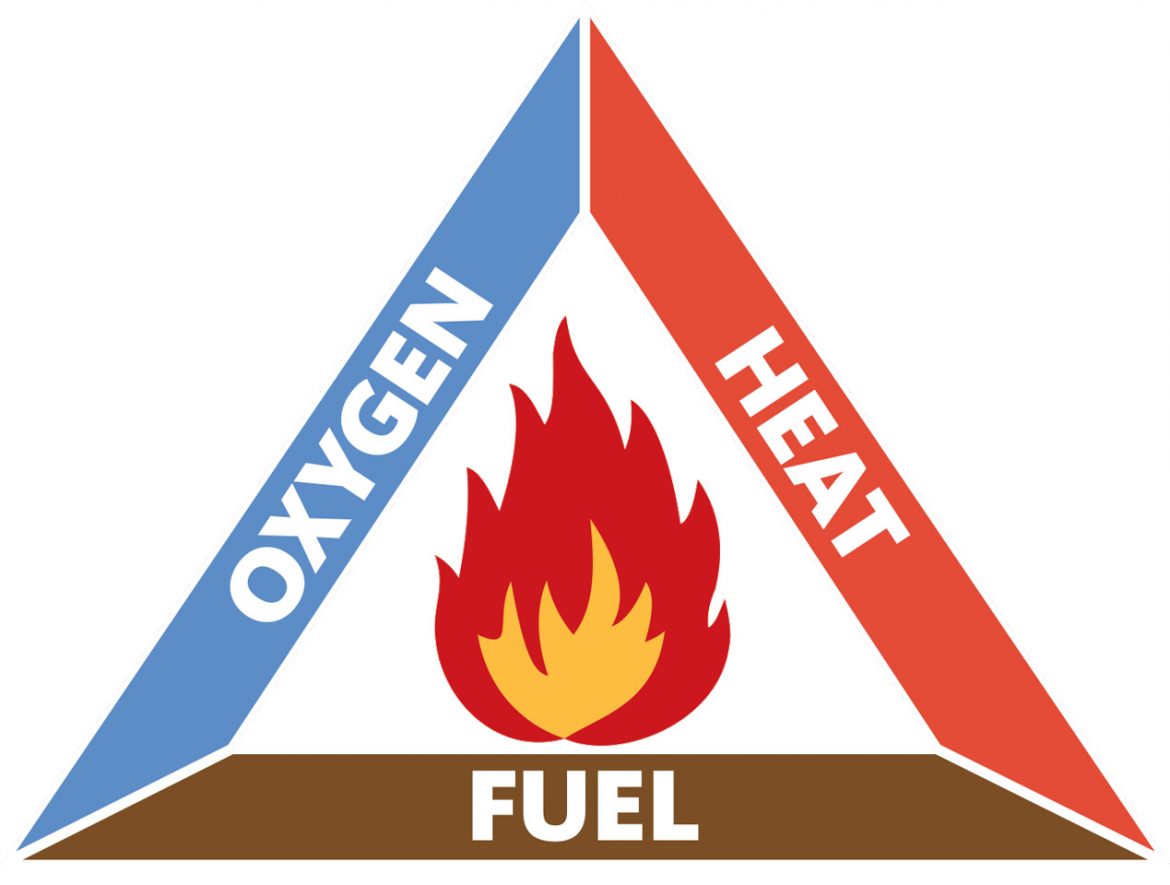

At its core, fire is a rapid chemical reaction that requires three key elements: fuel, oxygen, and heat, sometimes referred to as the fire triangle. If you remove any one of these elements, the fire cannot be sustained.

RVs contain an overabundance of fuel sources. They are made with large amounts of wood and composite materials that use extensive amounts of glues and insulating foams. They also have plenty of wiring, which has flammable insulation, and most have propane on board and — in the case of motorhomes — gasoline or diesel fuel. Of course, oxygen is readily available in the air, so all that’s needed to complete the fire triangle is heat.

Materials that serve as fuel need to be raised only to their combustible temperature for ignition to occur. An electrical short can create intense heat in a wire, which can burn insulation or ignite surrounding material wiring, which has flammable insulation, and most have propane on board and — in the case of motorhomes — gasoline or diesel fuel. Of course, oxygen is readily available in the air, so all that’s needed to complete the fire triangle is heat.

Materials that serve as fuel need to be raised only to their combustible temperature for ignition to occur. An electrical short can create intense heat in a wire, which can burn insulation or ignite surrounding material such as wood paneling or foam insulation. A loose connection can also throw sparks that ignite fuels. Gases or flammable liquids that reach open flames or hot surfaces can flash and ignite.

Fire Classifications

RVs are required to be equipped with a fire extinguisher, per National Fire Protection Association code. However, it only needs to meet the minimum requirements. So, fire extinguishers that come with RVs tend to be undersized and may not be equal to the task. While all fires may seem the same, they are not. Fires fall into three different classifications:

Class A fires use solid combustible fuels (other than metals), such as wood, paper, fabric, and plastics. Class A fires leave behind ash, so think of the word “Ash” to help remember what a Class A fire is. To extinguish a Class A fire, you can either separate it from its oxygen source or cool it to below its flash point. This is the easiest fire to extinguish, and water works well, because it cools the material below its combustible temperature. Ideally, adding an element to the water (soap works well) helps to break the surface tension and further separate the fuel from its oxygen, allowing the water to further cool the fuel and to suffocate it.

Class B fires involve flammable liquids, such as gasoline, oil, grease, diesel fuel, and alcohol. Liquids boil, so think of the word “Boil” to remember what Class B fires are. These fires can’t be extinguished with water, because the liquid fuel floats on the surface of the water and spreads to other areas, which only makes the situation worse.

Class C electrical fires are caused by energized circuits. If the circuit is live, consider it a Class C fire. Note that the wire itself doesn’t burn, but the insulation and things surrounding it do. Electrical wires conduct current, so associate the word “Current” with a Class C fire. Using a water-type extinguisher on a Class C fire can create an electrical shock hazard. Once the circuit is de-energized, however, you can treat it as a Class A fire.

Fire Extinguisher Ratings

Fire extinguishers are rated by an alphanumeric system. The letter stands for the fire classification(s) that the extinguisher is rated to handle, while the number in front of the letter indicates how large of a fire it is designed to handle. The number preceding the letter “A” is a water equivalency rating, with each A equal to the effectiveness of using 1¼ gallons of water. As an example, an extinguisher with a “2A” label is rated as effective as using 2½ gallons of water on Class A fires.

Fire extinguisher classifications

Class B and C extinguishers also have a number, but it represents the square footage that the extinguisher is designed to handle. For example, an extinguisher with a “10B:C” label is an extinguisher designed to handle Class B or C fires up to 10 square feet in size. It’s common to combine labels on a single extinguisher, such as “2A10BC.” Obviously, the larger the number, the better equipped you’ll be. You don’t want to run out of fire retardant before the fire is extinguished.

Fire Extinguisher Types

Fire extinguishers come in many types and sizes, and each is designed for a specific application.

Air Pressurized Water (APW): APWs are large tanks filled about 2/3 with water and pressurized with compressed air. When the trigger is pulled, the water exits the hose and nozzle like a giant squirt gun. APWs are used to extinguish Class A fires by taking away the heat. They are not to be used on Class B fires, where the water spreads the burning liquid and creates a larger fire. They also cannot be used on electrical circuits unless the power source has been removed. If the power is still on, the water can create an electrical shock hazard.

Carbon Dioxide (CO2): CO2 extinguishers are filled with highly compressed CO2 gas. The extinguishers have a hard plastic horn rather than a hose and nozzle, and as the CO2 exits, it sprays what is effectively dry ice on the flame. They operate by displacing oxygen from the fire, essentially suffocating the flame. A side benefit is that the CO2 is cold, so it also helps cool the fire. CO2 extinguishers are rated for use on Class B and C fires and generally are not effective on Class A fires, because they may scatter burning particles and may not displace enough oxygen to effectively smother the fire and prevent it from reigniting.

Dry Chemical: The most popular fire extinguishers available for consumer use today are the dry chemical variety. The dry chemical in these extinguishers resembles baking soda and is pressurized with nitrogen. The reason for their popularity is they can be used on Class A, B, and C fires. They function by coating the fire with a fine layer of chemical, separating the fuel from the oxygen. They also do not conduct electricity, so they are safe to use on electrical fires.

However, dry chemical extinguishers have their drawbacks. First, they leave a mess. The powder safely puts out electrical fires, but the chemical is toxic once heated and corrosive to electrical circuits. So, once the extinguisher is used, you’ll need to replace many of the electrical components. Dry chemical extinguishers also are of minimal benefit on Class A fires, and most RVs are filled with the combustible materials that make up that classification.

Even though these extinguishers are filled with nitrogen, the dry chemical will settle and pack together over time. A good recommendation is to turn the extinguisher upside down and whack the base with a rubber mallet every six months to keep the powder loose enough to be able to be expelled when needed. They also need to be checked regularly for pressure leaks, and they require servicing, although many of these units are inexpensive throwaways that are not serviceable. In that case, it’s important to replace them rather than keep around a nonfunctional fire extinguisher.

Clean Agent Gas: Halon fire extinguishers used an inert gas to displace oxygen in the area, smothering the fire. They have been banned in many areas because of atmospheric ozone depletion and are now being replaced by other, safer gasses. These are all referred to as “clean agent gas” extinguishers. Unlike halon, when they get hot they do not produce toxic gasses that could suffocate occupants. However, because they displace oxygen from the room, they should be used only in locations where people are not present. They are rated for Class B and C fires.

Aqueous Film Forming Foam (AFFF): AFFF extinguishers are used extensively by the military and firefighting services. AFFF is an agent that is mixed with water. When the material is sprayed through a nozzle, it leaves a foam blanket that prevents reignition. It operates by removing heat from the fuel as well as by cooling it down. It is effective on Class A and B fires.

High-Expansion Air-Compressed Foam: These extinguishers are filled with a designer foam that provides a viscous layer to block air from the fuel. It also emulsifies hydrocarbons such as gasoline or oil, rendering them inert so they cannot reignite. The foam exits at high pressure and clings to vertical surfaces, and it does not produce toxic gases. It has six times the penetrating power of AFFF, and it further helps to extinguish the fire by its cooling action, encapsulating the fuel source and changing its molecular composition to prevent it from reigniting. The designer foam is mixed with denatured water and is safe to use on Class A, B, and C fires.

The compact Fire Fight SS20 foam extinguisher works on small fires.

Extinguisher Basics

Keep in mind that you only have seconds to react when a fire breaks out. So, fire extinguishers need to be easily accessible. If you have only one, and it’s located at an entry door, should a fire break out between the door and the bedroom where you are sleeping, you won’t be able to get to it. The best practice is to keep an extinguisher in the bedroom, by the entry door, in the kitchen, and in an unlocked basement compartment. It’s also a good idea to add one to the towed or towing vehicle.

Handheld high-expansion air-compressed foam extinguishers are ideal for an RV. They don’t have the retardant packing issue that dry chemical units have, nor do they have the negative toxic effects on electrical equipment or humans. Small 16-ounce handheld units, such as Fire Fight’s SS20, can be strategically placed around the RV. At $30 each, they are quite affordable. For more firefighting capacity, Fire Fight’s six-liter SS450 handheld extinguisher costs $275, offers added run time, and can be refilled without having to send it back to the factory. A spare can of AFFF foam costs $30, and you fill the extinguisher with distilled water, add half of the can’s contents, and recharge it with compressed air.

Automatic fire extinguishers, such as this Cold Fire model, can be installed in an engine bay.

Automatic extinguishers have their place as well. Small, compact automatic extinguishers can be installed behind refrigerators, in generator compartments, or in engine compartments to detect and control fires. If a fire is detected, the extinguisher automatically sprays the area using a standard sprinkler-style head or a remote head attached to the cylinder via a stainless-steel braided hose.

One choice for controlling fires associated with RV absorption refrigerators, auxiliary generators, electrical control panels, etc., is the Proteng system, which uses nontoxic FM-200 clean agent gas. The unique thing about the Proteng, which had its origins in auto racing, is that the gas is precharged in sealed polyamide tubes that can be placed in key locations. No sensors, wiring, hoses, or sprinkler heads are used. When the tube reaches the designated temperature, it ruptures and expels the clean agent gas to smother the fire. The tubes come in various sizes and are specified for each RV. The Proteng system is sold exclusively by National Indoor RV Centers. Complete systems run from $159 to $1,399, but FMCA members receive a 10 percent discount; see www.fmca.com/proteng for details.

Proteng tubes filled with clean agent gas rupture when exposed to high heat.

An automatic extinguisher also is a good choice for engine compartments, although care must be taken with the type of extinguisher material used. For instance, clean agent gas isn’t the best choice for that location. Clean agent gas works by replacing the oxygen in the air. But engine compartments are not enclosed areas, and the gas is hard-pressed to fill that area effectively, especially if the engine is running and the radiator fan is moving air through the compartment.

An extinguisher that uses high-expansion air-compressed foam is better, as the foam coats the area and reduces the temperature to help control the fire. I use a four-liter Fire Fight system with two remote heads. I chose a system with larger-capacity cylinders to increase the run time. If the fire is large or allowed to continue undetected, a smaller cylinder may empty itself. If the engine is still running, the fire may reflash, and if the tank is empty, there won’t be any retardant to stop the fire. A larger tank provides more time to get off the road and shut down the engine. Automatic systems range from $400 to $695.

The automatic Fogmaker system applies a high-pressure mist of water to lower temperatures.

Another option for an automatic engine compartment extinguisher is the Fogmaker fire suppression system. The Fogmaker uses a high-pressure water mist that claims to decrease temperatures by 700 degrees Celsius within 10 seconds to lower the temperature below that required for combustion. A small amount of foam additive prevents hydrocarbon vapors from reigniting. A sensor connects to a warning display on the cockpit instrument panel.

In my opinion, all automatic fire suppression systems need some sort of sensor and remote alarm to be truly effective. This provides an early warning of the fire and allows time to address the situation. Professional alarms can be used, or something as simple as a 12-volt buzzer and flashing light on the dash works as well. An optional pressure switch does need to be mounted on the tank and can be added at a reasonable cost, but you need to specify this when ordering your system, because it’s not generally shown on the manufacturer’s website.

One major consideration with any fire is a reflash. Any fire can restart after being extinguished. For instance, if a diesel-pusher motorhome develops a fuel or hydraulic oil leak that ignites a fire, once the extinguisher has emptied, the fuel or oil will still be pumping, and the fire will reignite.

A dash-mounted alert system is an important accessory for automatic engine compartment extinguishers.

Smoke Alarms

An effective warning system can save your RV — or save your life.

With large RVs, it may take a while for smoke to travel from one end to the other. Therefore, it’s important to have multiple smoke alarms within the unit — one in the front and one in the back. Don’t place one too close to the cooking area, however, or you may be setting it off every time you burn the toast.

Smoke rises, so smoke alarms need to be mounted on or near the ceiling. Smoke alarms utilize either ionization or photoelectric sensing technologies. Ionization alarms are more responsive to flaming fires, whereas photoelectric alarms are more sensitive to smoldering fires. Each type works best in different situations. Fortunately, manufacturers make smoke alarms that incorporate both sensors in one unit.

Dual-sensor alarms such as the First Alert 3120B combine ionization and photoelectric technology.

Other Alarms

If an RV develops a leak in a propane line or an appliance, highly flammable gas can build up. Propane is heavier than air, so it settles near the ground, where it can creep along waiting for a pilot light or spark to ignite it. That is why propane gas alarms are mounted on an interior wall close to the floor.

Carbon monoxide (CO) is a byproduct of combustion and can come from fire, a furnace with a cracked heat exchanger, an exhaust system, or the exhaust from an auxiliary generator — yours or a nearby neighbor. CO is slightly lighter than air but doesn’t rise to the ceiling the way smoke does, so CO alarms usually should be mounted mid-wall. Many manufacturers now offer combination alarms, either a propane and CO alarm, or a smoke and CO alarm. The combination propane and CO alarms generally are located beneath the refrigerator, which is perfect for detecting propane, but may not be as effective for detecting carbon monoxide. Follow the manufacturer’s recommendations on the best location to place the alarm.

Since people are most vulnerable to the effects of CO poisoning while sleeping, it’s a good idea to have a detector near the bedroom.

Some CO alarms feature a digital LCD display that shows how much CO gas has accumulated. As little as 250 parts per million over an eight-hour period can be fatal, so a good alarm adds up the accumulative amounts, while less expensive models sound an alert only if a large amount of CO is present at one time.

CO and propane alarms become less effective over time, so these alarms should be replaced every 10 or so years, or as indicated in the user’s manual. The date of manufacture is stamped on the device.

Proper Preparation

Without a doubt, the most important factor when dealing with a fire is a calm mind. In an emergency, the mind always reverts to preparation, so rehearse what to do under any given situation. Discuss and practice how to deal with a particular fire and whether to fight it or exit the RV. Practice each escape route and method.

Outfit the RV with an adequate number of and the right type of fire extinguishers, knowing that the one small dry chemical unit that came with the RV probably won’t be enough. The same holds true for warning devices. Smoke, propane, and carbon monoxide alarms need to be properly located in order to be effective.

Knowledge is power. Attend a fire and safety seminar at an FMCA international convention. Attending one of these free seminars is the best investment of time you can make. You’ll gain immeasurable knowledge to help keep you safe

in your RV travels.

An RV Fire: Lessons Learned

Marc and Julie Bennett of RVLove.com bought a 23-foot 1973 Winnebago motorhome and, with the help of a local fire department, set it on fire with the goal of raising fire safety awareness among RVers. Watch how fast an RV can go up in flames. www.rvlove.com/fire

Sources And References

Fire Fight Products

(321) 299-5707

www.firefightproducts.com

First Alert

(800) 323-9005

www.firstalert.com

Fogmaker North America

(610) 265-3610

www.usscgroup.com/fogmaker-fire-suppression/

Kidde

(800) 880-6788

www.kidde.com

Proteng

(800) 210-0692

www.proteng.com/protect-my-rv

www.fmca.com/proteng

Oxygen, heat, and fuel are the three elements that must be present to support combustion. Eliminate one to extinguish a fire.