A national historical park reveals the consequences of a divided country, and the importance of reconciliation.

By Peter Smolens

September 2020

On April 9, 1865, in the small Virginia village of Appomattox Court House, Gen. Robert E. Lee, leader of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, surrendered his army to Union Gen. Ulysses S. Grant. It was the beginning of the end of the “war between the states,” which ripped the country apart for more than four years. During the conflict, at least 620,000 Americans died, more than in all of the country’s wars before and since. Another million were wounded.

Appomattox Court House, located east of Lynchburg, was little more than a cluster of buildings that spread across the Virginia Piedmont region. Like some other county seats at that time, it was named after its courthouse.

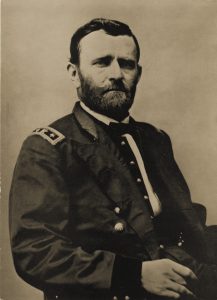

Union Gen. Ulysses S. Grant

The National Park Service has put together an impressive facility that includes indoor displays as well as a re-created town full of original buildings. The town appears very similar to what it looked like in 1865. The property pays tribute to both sides in the final days of the conflict.

In the center of the town is the rebuilt courthouse (the original burned down in 1892), which serves as the visitors center. Artifacts throughout the building include a list of all the men who were in the town at the time of the surrender. A 15-minute film shown upstairs in the courthouse explains the final days of the war from both the Confederate and Union points of view.

War’s End In Sight

Historians remind us that Lee was not the only Confederate general leading troops, and he did not represent the entire Confederacy when he surrendered. In fact, it wasn’t until May 5, 1865, when Confederate President Jefferson Davis dissolved his government. And the official declaration that the war was won by the Union didn’t come until August 1866.

But by late March 1865, Grant had put Lee’s army, already plagued by desertion, at a great disadvantage. Grant had cut off railroad lines that supplied food. The Battle of Five Forks, which some call the Waterloo of the Confederacy, was fought near Petersburg, Virginia, on April 1, 1865. Lee’s army was defeated and nearly a third of his men captured. After abandoning Petersburg, Lee’s men retreated to Amelia Court House, where they hoped to meet a Confederate supply train. But no train arrived. By that point, the men had not eaten for 36 hours.

The Battle of Sailor’s Creek on April 6 cost Lee another 7,700 men, and his son Custis was captured in heavy fighting. Lee headed west to another supply train stop outside Appomattox Court House. But the train had been captured by Union forces led by Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan and Maj. Gen. George Custer.

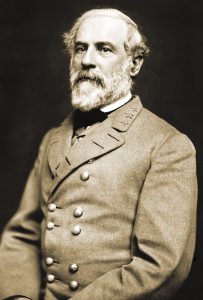

Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee

Yet another battle took place that evening near this site. Lee saw his supply lines cut off from the south, the James River to his north, and an army of starving men. He sent Grant a message requesting a meeting in the small village of Appomattox Court House at the most prominent house in town, owned by Wilmer McLean.

The Meeting

On the second floor of the courthouse, a copy of a famous painting by Tom Lovell depicts the meeting between the two generals that took place at the McLean House, just a short walk down the gravel road. In the home’s parlor on April 9, 1865, Lee and Grant met to discuss and sign surrender terms for the Army of Northern Virginia.

On that day, Lee arrived at the McLean home shortly after 1:00 p.m.; Grant followed 30 minutes later. Once they were in the parlor, Grant and Lee sat across from each other. Today, visitors can see authentic reproductions of the two small tables and chairs that sit about 10 feet apart.

It was decided that the terms of the surrender should be put in writing. Grant wrote out his terms in pencil and handed the paper to Lee for review. After reading the document, Lee made a few minor requests. Grant agreed to the changes. The final draft was put to ink, and duplicates were made for each side. Once completed, each man signed the documents. Afterward, they shook hands, and Lee left. The meeting lasted approximately an hour and a half. The original paperwork is held by the Smithsonian Institution and other museums.

A formal surrender ceremony, the stacking of the arms, took place on April 12. That gave the Union army time to print more than 28,000 parole passes that were distributed to the Confederate soldiers. Lee was worried that his army would reject the surrender and engage in guerrilla warfare. As part of Grant’s terms, passes were printed to allow the men to return home, free from detention.

A historical photo from the Civil War era

On that day, the Confederate soldiers walked up the hill between two lines of Union soldiers to, as a Park Service guide put it, “lay down their arms for the last time.” The place where guns were stacked, in front of what was then the Peers house, was called “Surrender Triangle.” Union Gen. Joshua Chamberlain accepted the formal surrender and later wrote: “On our part not a sound of trumpet more, nor roll of drum; not a cheer, nor word whisper of vainglory, nor motion of man standing at the order, but an awed stillness rather, and breath-holding as if it were the passing of the dead.”

The Park

On April 10, 1940, Appomattox Court House National Historical Monument was created by Congress. The start of World War II delayed its development, and on April 9, 1949, the National Park Service opened the McLean House to the public. The entire site, which encompasses approximately 1,800 acres, became a national historical park in 1954.

Visitors may be particularly struck by seeing the last days of the war from both sides. Periodically throughout the day during the summer months, interpreters play roles, such as a Confederate soldier who describes the last months of the war from his point of view. He notes that while they never lost pride in their cause, the lack of food was tough. On the other hand, a Union soldier explains that after Grant tightened his grip around the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia, they chased Johnny Reb west to this small town, beating the troops at every turn.

An interesting fact is that homeowner Wilmer McLean became wealthy as a sugar smuggler during the war, selling the commodity to the Confederates. All of his gain was in Confederate currency; when the war ended, McLean lost everything.

Once called the “Surrender House,” where the generals met, the McClean House opened to the public on April 9, 1949.

Several other historic buildings on the expansive park grounds can be seen via a self-guided walking tour. Overall, more than two dozen structures have been restored, and 31 others are awaiting restoration.

Inside the restored 1819 Clover Hill Tavern, you see a replica of the printing press used to create the parole passes for the Confederate soldiers. Built in 1819, it’s the oldest original structure in the museum.

A Stillness at Appomattox is the title of a book by historian Bruce Catton that details the end of the war. The park at Appomattox Court House is a tribute to the compassion, generosity, and honor both sides showed after four long years.

Area Camping

Check your campground app or directory, or FMCA’s RV Marketplace for more listings.

Holliday Lake State Park

2759 State Park Road

Appomattox, VA 24522

(434) 248-6308

Email: hollidaylake@dcr.virginia.gov

www.dcr.virginia.gov/state-parks/holliday-lake

Details

Appomattox Court House National Historical Park

P.O. Box 218

Appomattox, VA 24522

(434) 352-8987 ext. 226

www.nps.gov/apco

The park is approximately four hours southwest of Washington, D.C., and 25 miles east of Lynchburg, Virginia. Parking and admission are free. RV parking is available (no overnight parking). The visitors center is open daily from 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. Note: Parking areas, the courthouse/visitors center, bookstore, rest rooms, and living history programs are accessible. Many of the historical dwelling interiors are not wheelchair-accessible.

In season, living history talks are given by people portraying characters of the time. Ranger-led programs also are offered. A brochure with a map of the Appomattox Court House Driving Tour, with stops related to the surrender, is available; see the website for details. A helpful app also is available at the park website.