An informal history of the start of Family Motor Coach Association, written by the man whose vision and leadership resulted in the formation of what would become an international organization for motorhome owners.

By Bob Richter, L1

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the formation of Family Motor Coach Association on July 20, 1963, in Hinckley, Maine. From its humble beginnings in a field at a gathering attended by 26 families who came together to view a solar eclipse and to share their interest in travel by “house car,” to its status today as the world’s largest organization for motorhome owners, FMCA has touched many lives over the years. This article, penned by the late Bob Richter, provides a fascinating look at FMCA’s birth and infancy through the eyes of the man who had the insight to realize that a new era of travel had begun. Mr. Richter served as FMCA’s first president, in 1963 and 1964, and remained a strong proponent of FMCA and the motorhome lifestyle until his death in 1993. His wife, Jean, passed away in 2010.

It all started in our living room in Hanson, Massachusetts, in January of 1962. My wife, Jean, and I were discussing with her sister, Charlotte Neves, the concept of taking our family of six to visit relatives on the West Coast, and Charlotte said, “With your crew, you’d need a bus! Why don’t you get one, and we all can go?”

It sounded like a great idea. While Jean was at a League of Women Voters’ national convention in Minneapolis, Minnesota, in early May, I went shopping and came home with an old Greyhound, a 1940 General Motors pusher with 2,600,000 miles on it. We converted it that spring in minimal style, and used it with great success that summer and fall with our four children.

During our bus-buying, we met John and Jean Samuelson, later to become F19, and at that time from Hingham, Massachusetts, who introduced themselves by saying, “We’re the other bus nuts.” Next, we met Dr. George Whiting and his wife, Mary, later F7, of Abington, Massachusetts, who had a converted Flxible.

During our bus-buying, we met John and Jean Samuelson, later to become F19, and at that time from Hingham, Massachusetts, who introduced themselves by saying, “We’re the other bus nuts.” Next, we met Dr. George Whiting and his wife, Mary, later F7, of Abington, Massachusetts, who had a converted Flxible.

The only flaw in our otherwise delightful summer was when we attempted to park our bus overnight on a family-owned waterfront lot at the nearby seashore. From the reactions of the town government, we quickly learned that we were not welcome there; perhaps this prompted our first feelings that an organization of folks whose interests in travel paralleled ours might be welcome and worthwhile.

Soon we found we were making a list of people with rigs similar to ours, and at Christmastime we sent our six-color hand silk-screened Christmas card to the eight families we then knew of who had similar vehicles, inviting them to send us the names of other converted bus owners. Everyone replied, and we found that we soon had a small, growing list that showed that a broad-based interest might be developing.

Accordingly, on April 24, 1963, we sent out a mimeographed letter inviting the twenty-five families we then knew of to meet at a suitable spot (not yet determined) in Maine, to watch the total eclipse of the sun which was to take place on July 20th. Through a fortuitous previous personal friendship we found a marvelous meeting place on a hilltop at the Hinckley School in Hinckley, Maine, 200 miles north of Boston. The spot was great for watching the eclipse, but lacked most of the amenities expected now of even chapter meeting places.

On the way there in our bus with our family of six, plus Jean’s sister Charlotte — the initiator of it all! — and Marion Mott, later to become FMCA’s first office manager, we ran into a thundering deluge in Saugus, Massachusetts; our windshield wipers fell off in the middle of Route 1, and son Bill, then six years old, said, “Dad, you said we were going to Hinckley come hell or high water, right?” We were!

At Hinckley, we set up folding tables and chairs, strung recycled gas-station pennants from tree to tree for a festive note, and set up the abominable mimeograph for daily newsletters, a bulletin board, and two leaky and primitive toilet tents in a far corner.

At Hinckley, we set up folding tables and chairs, strung recycled gas-station pennants from tree to tree for a festive note, and set up the abominable mimeograph for daily newsletters, a bulletin board, and two leaky and primitive toilet tents in a far corner.

It was an experience impossible to describe as we first heard — and then saw — the twenty-six coaches arriving, one after another, with our new friends. The coaches varied from a simple school bus on its fifth engine, with only a mattress, crib, and stove in it, to a lush executive coach costing well up into six figures. What a sight to see them coming up the hill! And what great people!

What took place at Hinckley, in starting FMCA, is written up in my quite uncharacteristically solemn prose in the first issue of Family Motor Coaching magazine. But it was just the beginning of a very busy late summer and fall. Under the direction of the nine-member Constitutional Committee chosen at Hinckley, we drafted and finalized the FMCA Constitution and Bylaws, including the Code of Ethics, and it was unanimously ratified by the membership of 65 on December 15th, 1963. It is a tribute to the foresight of this committee that much of the basic framework remains as valid today as it did then.

The first issue of Family Motor Coaching magazine went to members in February of 1964. Getting that first issue out was an experience in mad logistics. The type was set in Brockton, Massachusetts, 8 miles from our home; carried to Hanson and proofed (for pasting up) on a rusty antique letterpress in a corner of our cellar, a few inches at a time, with the help of many friends, both old and new; then printed at the home of Dick and Nancy Parece, F22, in their cellar printshop in Natick, Massachusetts, 40 miles away, two pages at a time; and then assembled by a crew of volunteers circling around the Whitings’ pool table in the cellar of their Abington, Massachusetts, home, six miles away. The finished issues were trimmed in the cellar of a friend’s printshop in Hanover, Massachusetts, five miles in another direction, and finally came above ground to be mailed at South Hanson, four miles in another direction.

We printed, if I recall correctly, about 500, and had to reprint it a few months later; it was again reprinted in a later issue of Family Motor Coaching as a center insert. First-edition copies, which include the Blue Bird color insert, are as rare as hen’s teeth now!

The second issue of the magazine was pasted up here at our home, with the type set at Natick and the issue run by a large commercial printer. It was an aesthetic delight but a financial disaster, and nearly squashed the whole fledgling organization. In all, we did four issues; the difficulties are advertised inadvertently on the front covers. The first is dated “February 15, 1964”; the second, “June, 1964”; and the third and fourth, “Fall, 1964” and “Spring, 1965”!

FMCA really became a national organization at its first national convention at Fort Ticonderoga, New York, in July of 1964, and offered us an opportunity to learn a great deal about how to set up a large meeting. With little experience to call upon, we were very lucky that it turned out so well, and that the one hundred and six member families attending had such a great time. Future convention planners learned at Ticonderoga to avoid sites downwind from odoriferous paper mills, fields with hidden potholes that would swallow a motorcycle, and flies by day and mosquitoes by night that could carry off an innocent bystander! FMCA was in dire financial straits at Ticonderoga, and Ray and Anna Fritz, F4, and George and Mary Whiting, F7, went bus-to-bus soliciting donations to keep the organization afloat.

As FMCA grew and grew, it outgrew the room in our home where it had been housed, and we rented a small office at 1115 Main Street, South Hanson, for $65 a month. Soon we had three part-time employees, and the mail was coming in in baskets, sparked by write-ups in House Beautiful and other national magazines.

It was surely the case that, as FMCA grew, my personal fascination with the basic concept of the first totally new housing idea in 500 years — that of a self-propelled, self-contained, complete home on wheels — grew at equal speed. However, the electronics sales company I owned was paying our family’s bills but getting less and less of my attention and FMCA was becoming a totally demanding labor of love, never able to pay us for our work (which we would not have accepted anyway), or to repay us for our expenses. By the Spring of 1965, FMCA had grown to nearly 1,000 member families in every state of the United States but one, and in Korea, Canada, England, Italy, Saudi Arabia, and Australia. I was forced to face the reality of a choice between one and the other. It was no contest — electronics had to win, and FMCA was incredibly lucky in having Ken and Dot Scott, F63, of Cincinnati, willing to take over, and to do such a great job in making it grow and prosper.

We put over a ton of office equipment, supplies, and files — and a couple of bottles of pink champagne for two marvelous people, Ken and Dotty — in a moving van headed for Cincinnati on Friday, March 12, 1965, and reluctantly went back to the job of making money and raising children.

It had been a pretty rough two years, but we had made a host of new friends, learned a lot, and had earned the satisfaction that comes from having tried to make the world a bit better place to live in, for everyone.

Homes Of FMCA

-

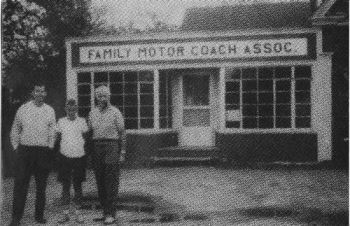

Charles Owens (left), F44, with Kenny Scott and his father, Ken Scott, F63, at FMCA’s original office in Hanson, Massachusetts.

Charles Owens (left), F44, with Kenny Scott and his father, Ken Scott, F63, at FMCA’s original office in Hanson, Massachusetts. - The Scott home, in an eastern suburb of Cincinnati, Ohio, served as headquarters from 1965-67.

- The “ivy-covered cottage” — located on Beechmont Avenue near the Scott residence — was FMCA’s rented home from 1967-70.

- FMCA’s next rented office was a few miles west of the cottage in a shopping plaza on Beechmont Avenue.

- A fund drive to pay for FMCA’s permanent national office at 8291 Clough Pike enabled the association to buy the building without a mortgage in 1976.

- To accommodate mail-forwarding operations and provide campground space, in 1989 FMCA purchased a facility on Round Bottom Road in Newtown, a few miles from the Clough Pike office.

-

The association’s iconic logo designates the national headquarters at 8291 Clough Pike today. The building was expanded and updated in the mid-1980s.

The association’s iconic logo designates the national headquarters at 8291 Clough Pike today. The building was expanded and updated in the mid-1980s.

History Of The FMCA “Goose Egg”

Family Motor Coach Association’s oval, goose-egg-shaped membership emblem has long been a part of the organization’s history. Members are provided these plates to display on their motorhome. Quite often, this membership emblem is the tool that initiates a conversation between motorhome owners at a campground or other location. It also promotes public awareness of FMCA.

New members of FMCA have been issued various types of coach plates over the years.

Early Plates

The first 10,000 members of FMCA, from 1963 to 1973, received cast-aluminum plates that had their membership number stamped on them in raised letters.

The first 10,000 members of FMCA, from 1963 to 1973, received cast-aluminum plates that had their membership number stamped on them in raised letters.

In 1973 the association began supplying numbered decals, made of weatherproof vinyl, to new members in lieu of the cast-aluminum plates. This change saved on the cost of material and prevented a membership dues increase. Metal plaques still could be ordered, for an additional charge to the member.

Also in 1973, FMCA’s leaders approved a provision for a “second generation” coach identification plate and number assignment. This allowed sons or daughters of active or former members to use their relatives’ membership number and request the addition of the letters “S” or “D,” centered below the number on their emblem. The current FMCA Bylaws expands upon this action by indicating, “FMCA shall, upon request, issue the original F number to sons, daughters, grandchildren, or parents of active or former members with the addition of an ‘S,’ ‘D,’ ‘G,’ or ‘P,’ respectively, centered below the number on the emblem.”

Switch To Acrylic

In June 1982, with the assignment of membership F44000, acrylic identification emblems were introduced. These new membership plates were injection-molded out of clear acrylic (Plexiglas). The membership number was engraved on the reverse side of the emblems and then decorated by hot stamping the black, and spraying white and then silver.

In 1994 FMCA was advised that the mold for the smooth acrylic plates had worn out. A new mold would have cost $30,000 to make, so FMCA decided to look for a new source material.

Today’s Plates

Beginning October 1, 1994, with the assignment of F185627, FMCA began issuing plates made of Lexan synthetic resin. The Lexan plates looked more like the original cast-aluminum goose eggs, but the letters and numerals were white and more visible. In 2012, as a cost-saving measure, FMCA began issuing plates that feature a high-gloss vinyl decal affixed to a Lexan plate.

FMCA membership numbers are never reissued and remain assigned to the original member. So, motorhomers who cease to be FMCA members keep their identification plates and can use them if they rejoin later.

These identifying numbers and plates are integral parts of FMCA, and members are asked to display their FMCA plates with pride.